21 Apr 3 things to know about people who live with disabilties

If you don’t have a disability yourself, how much do you really know about people who live with disabilities?

Are you aware of the ongoing battles for equality and employment rights in the UK? Chances are, if you don’t have a disability and none of your friends or family do, then you’re probably not totally up to date with the pressures facing this vast community of people.

What should you know from people who live with disabilties?

Stats from the Family Resources Survey 2019 show that there are at least 14.1 million people living with some form of disability in the UK alone. Detailed demographics consist of 8% of the child population, 45% of the pensionable age population and 19% of the working population all live with disabilties.

That’s a significant percentage of the UK’s total population. And yet legislation has been extremely slow. We had to wait for the Equality Act 2010 (Section 6(1)) to define disability formally. And while the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) of 1995 (ext. 2005) made it officially illegal for organisations to discriminate against disabled people within employment or education, the battle is far from won.

The later Equality Act replaced the DDA and covers other characteristics as well as disability. These include race, religion, sexual orientation and gender reassignment. Either way, despite this law and despite a lot of work to bring attitudes towards disabilties up to date, disabled people are twice as likely to be unemployed as those who aren’t disabled.

So, in 2021 there is still a long way to go to reach true equality for people who live with disabilties. But outside of legislation and the responsibilities of employers, what should everyone know about disability? As someone who has long lived with a physical disability, I wonder how much able-bodied people should expect us to explain. I wonder how much, by now, everyone should know about disability.

While the thinking around disability has obviously changed for the better over the past few decades, it’s still difficult to know how to approach the subject with people not directly impacted.

Three things to know about living with a disability

- ‘Disability’ is a really varied descriptive term

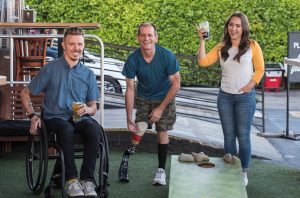

There are as many different types of disability as there are different people. No single disability is ‘better’ or ‘worse’ than another. No disabled person is impacted in exactly the same way as another. In other words, being disabled isn’t like being part of a homogenous group of people.

As every disability or conditions differs, so must the response and assistance given. All forms of disability form some kind of barrier, whether that’s between the person and the world of work, access to medicine, medical and mental hardships, the stigma faced in the outside world or finding help from the state, there is always a barrier.

People who live with disabilities do, therefore, share this in common. However, there are many differing attitudes towards different perceived levels of disability. This may be largely unacknowledged but remains true. For example, people with physical disabilties are generally accepted more readily by non-disabled people than people who live with mental disabilities.

Similarly, people who have cognitive impairment are quickly assumed to be far less capable of dealing with life. This is changing, but so slowly. People with learning disabilties or another less visible disability can be accepted but are often considered to be exaggerating or ‘faking’ their conditions.

This is, of course, a wide-ranging opinion. Of course, not everyone works this way, and these societal divisions are not set in stone. But they are clearly there. And this needs to change.

- All people who live with disabilties should be respectfully treated

Different responses are needed for different disabilties. People who are mobility impaired need decent equipment, wheelchairs and accessibility. Others may need some help to carry out everyday tasks. Blind and deaf people need devices to allow them to navigate the world around them, and to communicate.

People who live with chronic pain or illness need a world that understands and accepts the reality of their existence. One size very much doesn’t fit all when it comes to disability. But, on the flipside, different disabilties absolutely do not justify different prioritisation, different standards of respect or different human rights.

Adults are adults and should be communicated with as such, regardless of the type or level of their disability. It’s as simple as that.

- Living with a disability doesn’t mean life is terrible

People should know that the problems most disabled people encounter don’t come from their disability. They come from the society they live in and from the people they live around. Of course, disabilties bring their own challenges, but with a world properly equipped to allow disabled people to live their lives, many of these would be significantly reduced.

Indirect hardships stemming from disability come from other people – their ableism, systemic failures and poor accessibility, for example. Disabled people have to endure a lot, no doubt. But most of this comes from totally unnecessary pressure or lack of understanding from the outside world. Hardships caused by the disabilties themselves are very real, but everyone else can help people who live with disabilties by accommodating their needs and treating them like normal people.

Don’t get lost in the trap of thinking that disability is a tragedy that needs to be beaten. It’s not. This is an unhelpful attitude that views disability through a far too simplistic and fully ableist filter. Living as a disabled person isn’t one, single, easily identified experience common to everyone.

Rouzbeh Pirouz is Co-Founder and Senior Partner at London-based Pelican Partners, a real estate and private equity investment firm. On this website you can find out more about his life, work and experience.